Use Cases: The purpose of your code

Have you ever wondered to what extent your code expresses the business rules it supports?

Among all the things I have learned on the topic of software development, I would put the use cases at the very top of my must-to-learn disciplines for a software developer, and for the overall sustainability of a codebase in general.

Have you ever wondered to what extent your code expresses the business rules it supports? Who demanded them and why? How easy is it for a person to understand what your code does and where to get their hands on when it comes to changing a business requirement or supporting new ones? How difficult is it to understand the domain? Does your code speak of technical terms, or terms used by the business experts?

If you belong to that niche of people who believe that the domain should be well expressed in code and it should clearly reveal all its intentions, well, I think you’ve come to the right place.

Regardless of the codebase on which you are currently working, be it either a new codebase or a legacy code, either using frameworks or not, you are always right at introducing use cases in your code.

Use Cases are meant to be the very entry points to the application domain, they describe how domain actors interact with the application. They sit on the border between how the application communicates with the outside world and its domain. They are the first place to look when it comes to understand the purpose of the application, the domain, and all the business rules it supports.

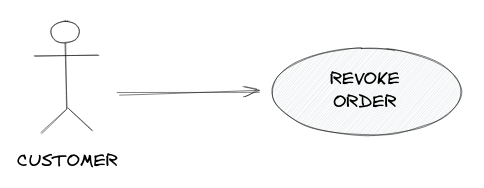

Fig. 1 - A Use Case UML Diagram

Let’s continue spending some more words on business rules, interactions, and how they can get translated into use cases, later in the next section.

Where are the business rules in your application?

The good news is that your code is already implementing all the necessary business rules. The bad news is that it’s not clear where all these business rules are, why they exist, and what role or domain actor they are serving. Everything is already in your code, it’s just scattered here and there.

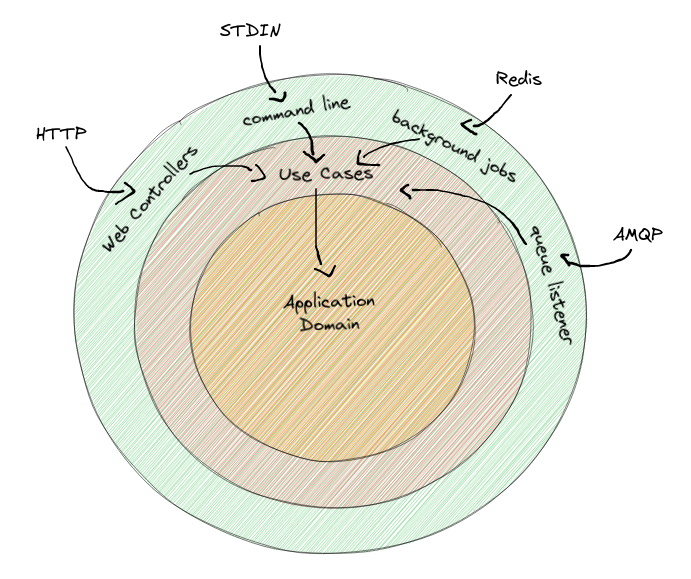

Chances are very high that business rules sit very close - and probably coupled - with the part of the code that triggers them. You might have business rules as part of web controllers, background jobs, queue listeners, ORMs, databases, and whatever. Sometimes you can have the same business rule duplicated here and there, but no clear space to keep them well organized and decoupled from the rest of your application.

I am telling this because I have been making this mistake over and over in a lot of projects where I worked, and I can still feel the pain of this mistake. To some extent I believe that if your code exists to support a complex domain, the absence of use cases should be considered a code smell.

A Use Case should not be coupled with the mechanism that triggers it. That said, a use case should know nothing about the detail of your web controller, or the background job, or the ORMs, or the queue listener. It’s quite the opposite, a web controller is responsible to make sense of the external request and know how to adapt it to a request for the use case.

We should always keep in mind the Dependency Rule Principle 1 as much as possible.

Source code dependencies must point only inward, toward higher-level policies.

A web controller is a lower-level policy compared to its use case. Thus, it should always depend on the use case, and the use cases should always depend on the application domain:

HTTP -> Web Controllers -> Use Cases -> Application Domain

Fig. 2 - Dependencies should point inwards.

Fig. 2 - Dependencies should point inwards.

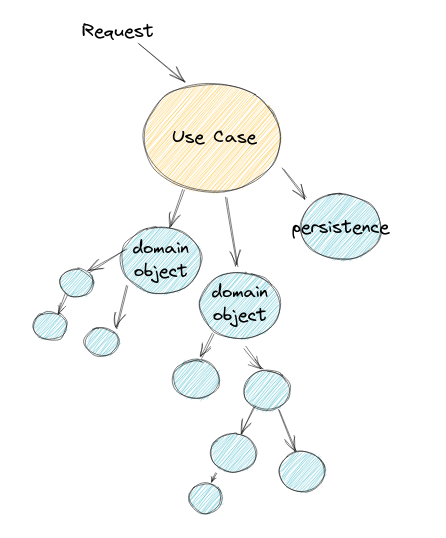

A Use Case should describe one and only one of the business rules supported by the application. They load the domain objects from the persistence mechanism, orchestrate them all to satisfy the request, and finally persist the changes.

Fig. 3 - How use cases orchestrate the application domain objects.

So far we have said that use cases should:

- Be the very entry point to the application domain.

- Describe how the domain actors interact with the application.

- Map one and only one business rule.

- Not coupled with the mechanisms that trigger them.

In the rest of this blog, we’ll see how to translate these concepts into real code, and explore a few desiderata that might be useful to remember.

How Use Cases are translated into code?

To make things clearer, I’m going to create a real-life scenario and just pretend for a while that we are working on an order management system. The domain is about making sure our customers can place their orders, track them, and perform several other actions on their orders.

Among all these actions, a customer should be able to revoke an order (see fig. 1), and when doing so, a set of business requirements have to be met:

- The order should not be already processed.

- A revoke reason should be attached to the order.

- Package shipping should be canceled.

The following is an example of this use case translated into code. I’m using Java, but as a small exercise for you, try to rewrite it using your favorite programming language, or rather, the programming language you’re using at work.

package com.foo.usecases

class RevokeOrder {

public RevokeOrder(Orders orders, WarehouseService warehouse) {

// ...

}

public RevokeOrderResponse call(RevokeOrderRequest request) {

Optional<Order> optional = orders.find(request.orderId());

if (optional.empty()) {

return RevokeOrderResponse.orderNotFound();

}

Order order = optional.get();

if (order.isProcessed()) {

return RevokeOrderResponse.orderAlreadyProcessed();

}

order.revokeWithReason(request.reason());

warehouse.cancelPackageShippingForOrder(order.id());

orders.save(order);

return RevokeOrderResponse.successfullyRevoked();

}

}

Fig. 4 - An example of use case translated into code.

Spend some time reading at the code, understanding what it does, what the domain objects are, and how well the business rule is described. Remember, the code above is just an example, it’s not a reference for your implementation. Once you are done I will tell you a few of the desiderata you might want to keep in mind when introducing use cases in your code.

Use Case desiderata:

- Use Cases should be organized in packages or namespaces. If you think the term usecases does not fit well with your code convention, you can always find better ones: interactors, actions, intents, businessrules, commands, application services (if you come from DDD). Try, discuss with your team and find the one that best matches your taste.

- At first, don’t try to organize your use cases into a package structure that is deeper than one level. Take some time to see what all your use cases are and only then understand how they can be well organized (by domain area, by actor, or whatever makes the organization clearer).

- The name of the use case should reveal the action that is about to happen on a specific domain object, so always choose an imperative form (verb-noun).

- Use cases are decoupled from the part of the system that triggers them, the callers should always depend on use cases (see

RevokeOrderRequest, andRevokeOrderResponse). Sometimes the response can happen in terms of callbacks instead of return values (see fig. 6 in the Appendix). - Use cases deals with the persistence (see

orders.find(request.orderId()), andorders.save(order)). - Use cases speak business terms, not technical terms.

Conclusion

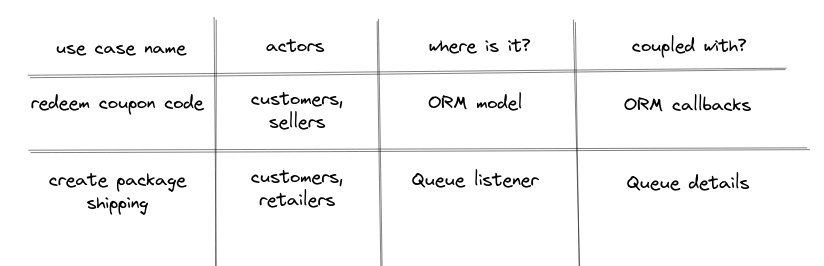

Using use cases can be a great benefit to the overall sustainability of your code, and it’s fun! Use cases are not something new. Much has already been explored there, so I’ll stop here, but if your team is considering adopting them, I’ll wrap up this blog by giving you a simple task to do.

Pick your code. Try to find and create a list of all possible use cases you see currently dispersed there, indicate which part of the code they are located, how much they are coupled with the rest of the application, and which domain area and actor they are serving.

Fig. 5 - Locate your use cases.

Fig. 5 - Locate your use cases.

This can be a good starting point for understanding the current state of the code, all business rules, and the domain it supports.

References

- Watch Crafted Design

- Read Hexagonal Architecture

- Read The Clean Architecture

- Read Screaming architecture

- Read the book Clean Architecture

Appendix

Using callbacks instead of return values

package com.foo.usecases

class RevokeOrder {

public RevokeOrder(Orders orders, WarehouseService warehouse, RevokeOrderPresenter presenter) {

// ...

}

public void call(RevokeOrderRequest request) {

Optional<Order> optional = orders.find(request.orderId());

if (optional.empty()) {

presenter.orderNotFound(request.orderId());

}

Order order = optional.get();

if (order.processed()) {

presenter.orderAlreadyProcessed(request.orderId(), order.processedAt());

}

order.revokeWithReason(request.reason());

warehouse.cancelPackageShippingForOrderId(order.id());

orders.save(order);

presenter.successfullyRevoked(request.orderId());

}

}

Fig 6 - Using callbacks instead of return values.